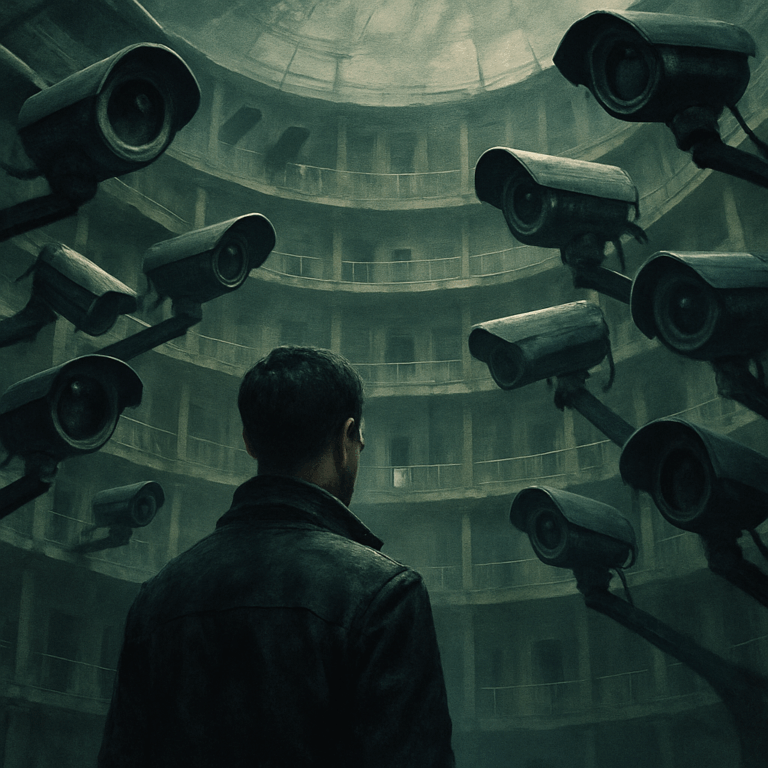

Modern society is often compared to an invisible prison without bars – a place where we constantly feel the panoptic gaze of cameras, authorities, peers, and even ourselves. Panopticism, a concept born of an 18th-century prison design and later expanded by philosophers, describes how people under surveillance begin to police their own behavior.

In today’s world of CCTV cameras, phone tracking, and social media, this phenomenon is more relevant than ever. We have, in a sense, become both the watched prisoners and the watchful wardens of our own behavior.

This article takes a deep dive into Panopticism and the psychology of control – examining how the mere possibility of being watched can fundamentally alter our actions, for better or worse. We will explore the origins of the idea in Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, Michel Foucault’s influential analysis of surveillance and power, and the latest research on how surveillance (and even the hint of it) leads to internalized self-discipline. Perspectives from both mainstream supporters of surveillance and its critics will be discussed in a nuanced way.

Finally, we connect historical Panopticism to its modern digital counterparts, asking what it means for personal autonomy and freedom when we carry a virtual panopticon in our pockets every day.

The Origins of Panopticism: Bentham’s Panopticon

To understand Panopticism, we begin with its literal foundation: the Panopticon. The Panopticon is an architectural design for an institutional building – famously, a circular prison – conceived by English philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century. Bentham’s idea was simple but radical: build a round house of incarceration with a central watchtower and peripheral cells. In this configuration, a single watchman in the tower can observe every inmate, “without the inmates being able to tell whether or not they are being watched.”

The cells around the circumference are flooded with light, each prisoner fully visible from the center, while the tower’s windows are darkened or screened so that inmates never know if a guard is present and looking. As Bentham described, the scheme allows “all (pan-) inmates of an institution to be observed (-opticon) by a single watchman.”

The genius (and insidiousness) of this design is that although one guard obviously cannot see everyone at every moment, the prisoners must act as if they are being watched at all times. Bentham wrote that since inmates cannot discern when they’re under observation, “they are motivated to act as though they are being watched at all times. Thus, they are effectively compelled to regulate their own behaviour.”

In other words, the constant possibility of observation would internalize discipline within the prisoner. This self-regulation is the crux of what later came to be called Panopticism – a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.

Bentham was a social reformer who believed his design could be a humane and efficient way to manage not only prisons but also schools, hospitals, asylums, and factories. He imagined a wide application for what he termed the “inspection principle.” In his view, visibility could replace violence in enforcing rules.

Bentham famously described the Panopticon as “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example.” The Panopticon, he hoped, would be a cost-effective deterrent to bad behavior: one guard could control hundreds of inmates, as each inmate, unsure if they were being observed, would internalize the gaze of the guard and behave.

In one vivid phrase, Bentham called his envisioned prison “a mill for grinding rogues honest”, reflecting his belief that constant surveillance would reform morally wayward individuals. This architectural solution was intended to induce in the inmate “a state of conscious and permanent visibility” that assures the automatic functioning of discipline.

Historically, Bentham’s Panopticon was never built exactly as he designed (Bentham struggled for years to get his prison plan adopted). Nevertheless, the idea proved immensely influential as a metaphor for modern surveillance and control. By the 19th century, elements of the Panopticon’s design (such as radial prison wings and central observation halls) appeared in many prisons in Europe and the United States, albeit not perfectly realizing Bentham’s ideal of total visibility.

Bentham’s core insight – that uncertainty about being watched can discipline individuals far more efficiently than chains or guards on every corner – has endured. He recognized that power executed through observation is both subtle and potent: visibility itself becomes a trap.

As we shall see, this concept of self-policing under an unseen eye lies at the heart of Panopticism.

Read more about it here.

Panopticism in Theory: Michel Foucault’s Analysis of Surveillance

While Bentham invented the Panopticon, it was Michel Foucault, a 20th-century French philosopher, who took the idea of Panopticism to a new level of social theory. Foucault’s 1975 book Discipline and Punish examines the birth of the modern prison system – and with it, the birth of a society that disciplines itself.

In a famous chapter titled “Panopticism,” Foucault uses Bentham’s Panopticon as a powerful metaphor for how modern power operates. He argued that from the 18th century onward, society underwent a transformation into a “disciplinary society” characterized by pervasive surveillance and normalization.

In Foucault’s analysis, the principles of the Panopticon – visibility, unverifiability, and internalized surveillance – spread beyond prisons to factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, and everyday life. Foucault described Panopticism as a general principle of social control: many individuals can be controlled by very few supervisors if those individuals believe they are under constant observation.

He famously wrote, “Visibility is a trap.” In the Panopticon design, each person “is seen, but he does not see” the observer – power is both “visible and unverifiable,” visible in the looming central tower yet unverifiable since the subject never knows when they’re being observed. The result is an automatic, self-imposed discipline.

Foucault noted, “The Panopticon induces a sense of permanent visibility that ensures the functioning of power.” The genius of this system is that actual surveillance can be discontinuous – the guard may or may not be watching at any moment – but the effects of surveillance are permanent. In Foucault’s words, “Surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action.” Because the person knows they could be watched at any time, they behave all the time.

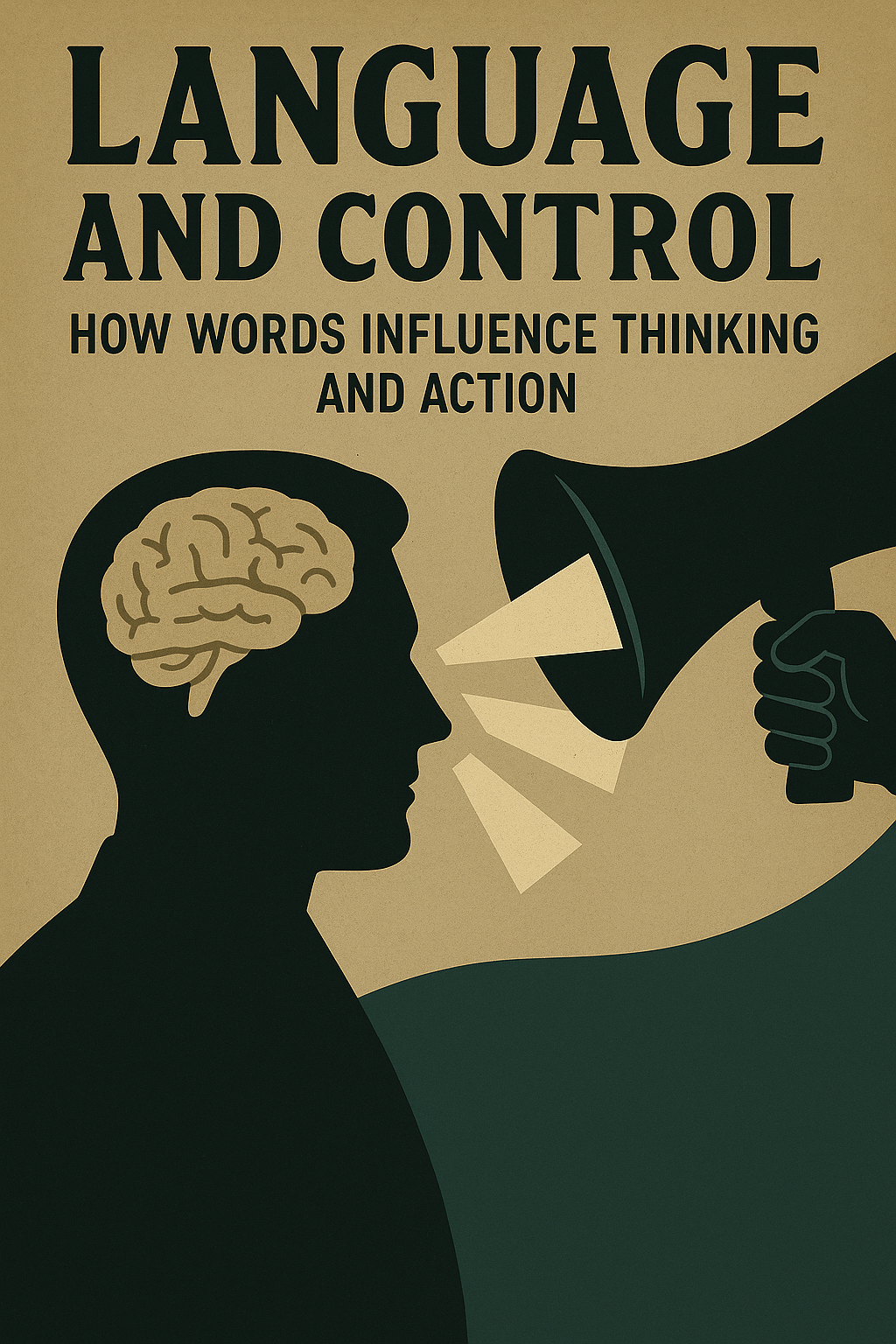

At the psychological core of Foucault’s Panopticism is the idea that people ultimately internalize authority. He writes, “He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power… he becomes the principle of his own subjection.” In other words, under constant potential surveillance, we effectively become our own guards. We monitor ourselves, adjusting our actions to conform to whatever norms or rules the power-holders desire, even when no one is actually watching.

In Foucault’s view, this represented a profound shift in how power works: rather than through obvious force or spectacle (like a public execution in pre-modern times), modern power works invisibly, inscribing itself into our very minds and behaviors. Panopticism, as Foucault defined it, is “a laboratory of power” – a social mechanism that renders external enforcement almost unnecessary because people enforce upon themselves.

Foucault extended this analysis to society at large. He pointed out that schools, factories, military barracks, and hospitals all started adopting layouts and practices echoing the panoptic principle (e.g., supervisors overseeing many individuals, examinations and record-keeping, etc.). By the 19th and 20th centuries, Western society had built what he called “a carceral archipelago” – a network of institutions all disciplining bodies and minds in panoptic fashion. The end goal was “docility and utility”: citizens who behave predictably, productively, and obediently.

The Panopticon for Foucault was not merely a prison design but “a diagram of power reduced to its ideal form,” a model for how to structure society such that social control is internalized.

Importantly, Foucault’s tone was critical and analytical, not celebratory. He illuminated how such surveillance-based discipline can suppress individuality and freedom, even as it produces order. He also noted an interesting paradox: in Bentham’s ideal Panopticon, not only are the prisoners observed by the guard, but the guard tower itself could be subject to oversight by authorities (or the public) to ensure no abuse – a kind of “Who watches the watchers?” scenario.

In this way, the Panopticon was supposed to prevent tyranny as well as disorder. Nonetheless, Foucault and others have argued that this system carries a heavy psychological toll and raises ethical questions.

We will explore those debates later. For now, Foucault’s contribution was to give us the term “Panopticism” as a way to understand a key psychological mechanism of control in modern life: that through surveillance, external power can become internal self-restraint.

Read more about it here.

From Surveillance to Self-Surveillance: The Psychology of Panopticism

Why do people change their behavior when they know they’re being watched? The answer lies in basic human psychology. Panopticism’s power is ultimately psychological: it works on our minds, inducing self-discipline.

When we sense an “eye” watching (or even might be watching), we tend to adhere more closely to social norms, rules, or expectations. Psychologists have studied this surveillance effect in a variety of contexts, confirming that the panoptic principle isn’t just an abstract theory – it’s a measurable human response.

One striking example is the “watching-eye effect.” Research shows that people behave more honestly and pro-socially in the presence of images that depict eyes. In experiments, merely hanging a poster with a pair of human eyes in a communal area can reduce littering or increase contributions to an honesty box for coffee payments. The eyes aren’t real, of course, but they trigger the feeling of being observed.

According to a summary of studies, even a simple depiction of eyes is enough to elicit the sense of being watched, leading individuals to be more honest and exhibit less antisocial behavior. This almost subconscious reaction highlights how deeply surveillance (or the illusion of it) taps into our social conditioning. We are highly sensitive to others watching us – so much so that our brains respond to a symbol of watching as if it were actual surveillance.

Another well-known phenomenon is the Hawthorne effect, named after industrial studies in the 1920s: individuals temporarily improved their work performance simply because they knew researchers were observing them. While the Hawthorne effect has been debated, it underscores the general principle that people alter their conduct under observation, often to present themselves in the best possible light.

Similarly, studies in offices have found that installing visible monitoring (like CCTV or keystroke trackers) can lead employees to arrive on time more and take fewer obvious breaks – essentially, they self-police to avoid looking bad. However, interestingly, if surveillance is overbearing, it can also backfire (more on that in a later section).

The key psychological mechanism at work is self-awareness. When we know someone might be watching or judging, we become more self-conscious. We compare our actions to expected norms and often suppress impulses that might attract negative attention or punishment. It’s as if an “inner camera” switches on in our minds whenever an actual camera (or authority figure) is in sight.

Over time, repeated experiences of surveillance can make this inner camera permanent. We carry the watcher’s gaze within us, monitoring our own compliance even in situations where we are alone. This is exactly what Foucault meant by the internalization of the panoptic gaze: we enforce the rules on ourselves. The prisoner in a panopticon ultimately doesn’t need guards; “…each prisoner self-regulates, in fear that someone is watching their every move.”

Psychological research provides plenty of real-world illustrations. In one study, participants were less likely to cheat on a test or game if they were told a fictional invisible person named “Princess Alice” was in the room watching – a scenario used to study children’s honesty. The fact that even an imaginary watcher inhibited cheating speaks volumes: our minds respond strongly to the idea of an observing presence.

(This has even been theorized to relate to religious belief – the notion of an all-seeing deity may function as a kind of cosmic panopticon encouraging believers to behave morally, even when no other human is around.)

In everyday life, think of how we act when a police car is driving behind us: almost everyone will rigidly follow the speed limit and traffic laws, effectively policing themselves. The same driver, alone on an empty road, might roll through a stop sign – but under perceived surveillance, they adhere to the strict letter of the law.

Surveillance shifts the locus of control from external enforcement (“I better not get caught”) to internal (“I shouldn’t do this because someone might be watching”). Over time, this can lead to habitually cautious or conformist behavior even when surveillance is absent.

It’s important to note that this internalized surveillance can carry emotional consequences. Constant self-monitoring can create stress and anxiety. The individual may feel a loss of spontaneity or freedom – a sense that they must always “watch themselves” lest they slip up.

Psychologists have observed that people who feel under continuous observation can experience diminished creativity and a fear of standing out, as they fall into meekness and conformity under the ‘chilling effect’ of surveillance. A classic example is how we might refrain from googling certain contentious or embarrassing topics at home because we know our internet activity is recorded. We censor our curiosity out of an internal fear: “What if someone found out I searched for this?”

In the following sections, we’ll explore how this dynamic plays out on a large scale, and the ways it is praised or criticized.

Read more about the psychology of being watched here.

Surveillance in Society: Mainstream vs. Alternative Views

The idea that surveillance leads to self-discipline can be interpreted in two very different lights. On one hand, it promises a safer, more orderly society – if people behave themselves even when no authority is visibly present, rules are followed and harm is prevented. On the other hand, it rings alarm bells about privacy and personal freedom – if people feel they must censor and conform at all times, creativity, dissent, and individuality may be stifled.

In modern debates about surveillance (from CCTV cameras in cities to government monitoring of the internet), we see these mainstream vs. alternative perspectives clash.

Mainstream View – Security, Order, and Accountability:

Many authorities and citizens view surveillance as a necessary tool for safety and governance. The argument often goes: If you’re not doing anything wrong, you have nothing to fear from being watched.

Constant CCTV monitoring in public spaces, for example, is credited with deterring crime and antisocial behavior. Indeed, studies have shown that installing visible security cameras in crime-prone areas can lead to a significant drop in offenses – people “think twice” about breaking the law when they know a camera is recording them.

For instance, an Urban Institute study in American cities found notable reductions in local crime after surveillance cameras were introduced. In surveys of convicted criminals, more than half said the presence of security cameras deterred them from choosing a particular target, ranking cameras as the #1 deterrent against crimes like burglary.

These findings support the idea that panoptic effects can be socially beneficial: would-be wrongdoers police themselves, and society is safer as a result.

Beyond crime prevention, proponents argue that surveillance brings accountability. Police body cameras, for example, not only make officers mindful of their own conduct (knowing they are recording themselves) but also provide transparency to the public. Likewise, employee monitoring in workplaces – when done within reason – is justified as a way to ensure productivity and prevent misconduct like theft or harassment.

The mainstream stance emphasizes that surveillance, when properly managed, protects the law-abiding. It can also equalize enforcement: if everyone knows the traffic light has a red-light camera, everyone is compelled to stop, not just those in sight of a police officer.

In short, supporters see a well-designed panoptic system as efficient and fair – a continuous gentle nudge for people to do the right thing.

Alternative View – Chilling Effects, Privacy Erosion, and Power Imbalance:

Opponents of pervasive surveillance focus on the subtle, long-term costs of living under the panoptic gaze.

Privacy advocates warn that when people know they are (or could be) watched, they often become more timid and compliant. This chilling effect can discourage not only illegal acts but perfectly legal, even important acts – like researching unpopular political ideas, exploring one’s sexuality, or engaging in dissent.

The revelations by whistleblowers about mass government surveillance (e.g., the Edward Snowden disclosures in 2013) provided real-world evidence for these concerns. After learning about the NSA’s monitoring programs, a significant percentage of Americans reported that they changed their behavior: about 1 in 6 said they avoided using certain search terms or websites for fear of drawing attention.

Wikipedia searches for topics like “al-Qaeda” and “Taliban” dropped by 20% after the news broke, presumably because ordinary people didn’t want their curiosity misconstrued as suspicious.

In a democracy, such self-censorship is deeply problematic – it means fewer citizens inform themselves or speak openly on issues, narrowing the range of debate. As one journalist, Glenn Greenwald, put it: “People act differently when they know they’re being watched. Essential to what it means to be a free and fulfilled human being is to have a place where we can go and be free of the judgmental eyes of other people.”

Critics also point out that constant surveillance can create a climate of fear and mistrust. Knowing that every move might be recorded or judged, individuals may stick to safe, conventional choices. This could lead to a society of conformity, where deviation – even harmless originality or protest against injustice – is discouraged.

There is also the matter of power: who is doing the watching, and will they use that power fairly? History and literature (from Orwell’s 1984 to real totalitarian regimes) show that surveillance concentrated in the hands of a few can enable gross abuses.

The internalized warden inside each person, planted by surveillance, might enforce not just benign laws but also unjust policies. For instance, in an authoritarian context, citizens might not voice dissent or assemble lawfully because they fear they’re being tracked and will be punished. Thus, self-policing serves the oppressor.

Even in workplaces, an overly monitored employee may feel dehumanized and rebel in hidden ways (studies have found that employees under extreme surveillance sometimes engage in more misbehavior as a form of backlash or reduced trust).

It’s worth noting that neither perspective entirely rejects the importance of the other. Even privacy advocates acknowledge that targeted surveillance (with proper oversight) can be legitimate for public safety, and even the most pro-security voices typically accept that some privacy is vital for a free society.

The debate is about balance and scope. How much surveillance is too much? At what point do we cross into a Panopticon that truly “turns us into our own wardens,” to the detriment of our liberty?

These questions have only become more complex with the advent of digital technology, which we turn to next.

Read more about mass surveillance and society here.

Modern Digital Panopticism: Surveillance in the Internet Age

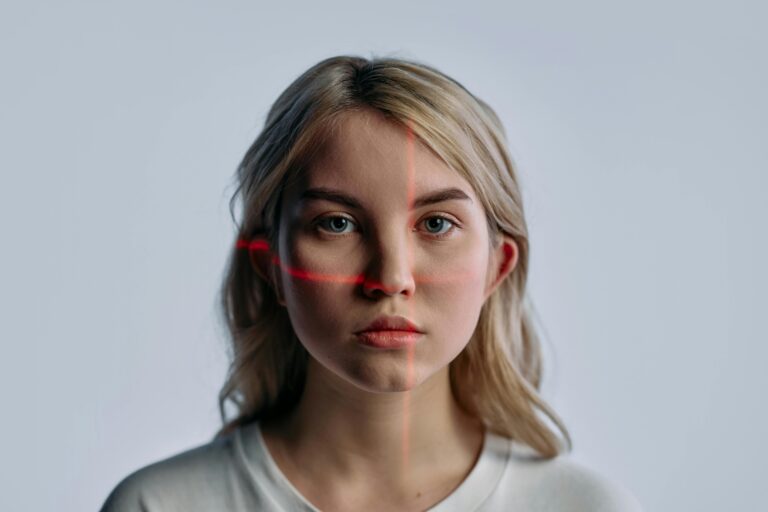

In the 21st century, the Panopticon is no longer a mere architectural blueprint – it’s a metaphor for our digital lives. Modern technology has created a pervasive form of surveillance that Bentham and even Foucault could only begin to imagine.

Today’s “watchtowers” come in the form of server farms and algorithms, CCTV networks, smartphones, and social media platforms. And rather than a single watchman, there are many observers: governments, corporations, and even our peers.

This digital panopticism has further blurred the line between external monitoring and self-surveillance, as we increasingly participate in our own surveillance.

Consider social media. On platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter (now X), people knowingly share personal information, their opinions, photos, and daily activities. We do this voluntarily, but not without a keen awareness of an audience. Friends, family, coworkers, and strangers form a kind of distributed surveillance network, each with the potential to judge or react to our posts.

The result? Many users end up curating their online presence carefully – essentially self-censoring and self-policing their content.

Psychologists have found that a large majority of users engage in “last-minute self-censorship” on social media: typing out a comment or status update and then deleting it before posting. Why? Because we anticipate the panoptic gaze of our network. We worry how others (or even the platform’s moderators or future employers) will perceive us.

This is Panopticism at work in a new guise: the internal moderator in our head that asks, “Should I really say this, knowing it will be recorded and visible to all?”

Beyond peer scrutiny, there’s corporate and state surveillance. Internet companies track our clicks, searches, and purchase history minutely – creating detailed profiles to target ads (a practice sometimes dubbed “surveillance capitalism”). Government agencies may monitor communications en masse looking for security threats.

The knowledge (or even suspicion) of these activities can cause ordinary people to modify their behavior. For instance, after learning about government eavesdropping, people might avoid visiting controversial websites or “avoid using certain terms online,” as mentioned earlier, for fear of ending up on some watchlist.

In countries with extensive internet censorship and surveillance – say, China with its Great Firewall and social credit system – individuals must be extremely mindful of what they say in chats or how they behave online, since those actions can be recorded and have real-world consequences.

Over time, this leads to a population that exercises preemptive self-restraint in line with government expectations – a massive, digital-age realization of Panopticism’s ideal of people disciplining themselves.

Smartphones deserve special mention. These ubiquitous devices are effectively tracking devices we carry everywhere. Location services, app usage, microphones and cameras – all can potentially be used to surveil. Even if one trusts that these data are only used for innocuous purposes, the perception of being monitored is widespread.

It’s not uncommon to hear someone joke (half-seriously) that “my phone is listening to me” after they get an uncannily relevant advertisement. That perception contributes to a panoptic ambiance in society: an assumption that nothing we do with technology is truly private.

The result is what some scholars call the “chilling effect” on digital speech and behavior, akin to a modern Big Brother scenario. People might speak differently on a phone call than in person, knowing the call could be logged. They might avoid searching certain keywords, as studies showed after 2013. Or they use euphemisms and coded language to discuss sensitive topics online, effectively policing their own speech to avoid automated flags.

Yet, unlike Bentham’s one-way gaze, the modern digital Panopticon has a twist: we are also watchers.

Through social media and ubiquitous cameras, citizens are surveying each other and even those in power. This has been called the “synopticon” by some sociologists – where the many watch the few – exemplified by people filming police misconduct or sharing information about elite actions.

However, even this phenomenon often feeds back into self-discipline. Knowing that anyone can record you at any time (in public, every smartphone is a potential surveillance device) makes many people more careful about their public behavior. A single outburst or mistake could be caught on camera and go viral, leading to social or professional repercussions.

Thus, we internalize not just the state’s or company’s gaze, but the gaze of society at large.

In this digital world, Panopticism has become crowdsourced and automated. We carry the Panopticon in our pocket, and we check on it voluntarily. We align our behavior with the expectations of multiple invisible audiences.

As Foucault noted, the effect is that surveillance becomes permanent in its consequences, even if we are not literally watched every second. A tweet posted years ago can resurface and “judge” you in the present; an algorithm might not flag your post today, but it could in a future political climate. So, prudent people learn to continuously self-filter.

Some thinkers argue this leads to a loss of authenticity. Are we truly free to be ourselves if we’re constantly performing for an imagined camera?

Others point out the benefits: perhaps it makes us more civil and polite, knowing our actions are effectively part of a public record. Just as a driver might drive more safely with a dashcam on, perhaps society behaves a bit better when aware of the panoptic web around us.

Either way, the psychological shift to self-surveillance is unmistakable in the digital age. We have all, to some degree, become our own wardens, monitoring and correcting ourselves as we navigate the vast, open prison of information networks.

Read more about mass surveillance in the digital era here.

Criticisms and Limitations of Panopticism

While Panopticism is a powerful lens to examine surveillance, it is not without its critics and limitations. Human behavior and society are complex, and not everyone reacts to surveillance in the same uniform way.

One criticism is that the “panoptic effect” might be overstated or uneven – some individuals or groups simply do not internalize the watcher’s gaze to the degree Foucault’s theory suggests. For example, determined criminals often find ways to evade or ignore surveillance (masking their identity, exploiting blind spots, or using encrypted communication). The presence of CCTV might deter opportunistic crimes, but it may have less effect on crimes of passion or those undeterred by consequences.

Studies on public surveillance cameras show mixed results: overall crime can drop, but some offenders just shift to areas out of view, or eventually become desensitized to cameras when they perceive that “no one is actually watching live” (cameras often record passively unless actively monitored).

Another limitation is the potential for surveillance to breed counter-behaviors. As mentioned, workplace studies have intriguingly found that excessive monitoring can erode trust and loyalty. In one Harvard Business Review study, employees who felt heavily monitored were more likely to break rules or slack off in covert ways, as if to reclaim a sense of autonomy.

This is a paradox: instead of self-disciplining positively, they rebelled against the surveillance. Such findings suggest that if people feel surveillance is unjust or overly intrusive, they might not internalize its norms; instead, they may develop resistance strategies (like using privacy tools, forming secret codes, or in the work example, deliberately working slowly when out of camera view).

Critics of Foucault, like sociologist Anthony Giddens, have also argued that his vision of Panopticism underestimates human agency. Real people are not passive dupes of a surveillance system – they negotiate, interpret, and sometimes subvert the rules.

For instance, students in a strict school might appear compliant but find subtler ways to express individuality out of the teacher’s sight. Or citizens may engage in “privacy protests” – deliberately feeding false data to surveillers, or using humor and subculture as a form of pushback.

The digital era has indeed seen the rise of encryption, anonymity networks, and other means by which individuals try to carve out spaces free from the all-seeing eye. The mere existence of these tools is evidence that not everyone consents to be their own warden 24/7; many people still crave and actively seek corners unlit by surveillance.

Additionally, the psychological toll of constant self-discipline is a concern. Mental health experts warn that if someone feels they must be perfect under observation at all times, it can lead to chronic anxiety, stress, and a diminished sense of self. People might start to define themselves only through the eyes of others (“What do they expect me to be?”) and lose touch with their own desires or creativity.

Society as a whole could suffer if the fear of surveillance chills innovation and the questioning of authority. Historically, some of humanity’s greatest ideas and social progress have come from rebels and whistleblowers – individuals willing to defy norms.

If Panopticism is too effective, could we risk smothering the sparks of positive change?

For example, Bruce Schneier, a security expert, noted that pervasive surveillance leads people to self-censor and stay well within the lines: “If you don’t know where the line is, and the penalty for crossing it is severe, you will stay far away from it. Basic human conditioning.” While this may maintain order, Schneier argues it’s “the worst effect” of surveillance, because it can halt the natural social progress that comes from questioning and deviating from the status quo.

He points out that movements from civil rights to LGBTQ+ rights needed private spaces to discuss and dissent before they could bloom in public. In a world where everyone is their own warden, those crucial subversive conversations might never happen.

In summary, Panopticism as a theory brilliantly highlights how surveillance can lead to self-governance. But it isn’t a one-size-fits-all description of human behavior. People are capable of compliance and resistance, often simultaneously. Surveillance can guide behavior, but it can also distort or provoke it in unexpected ways.

And crucially, the moral evaluation of Panopticism is double-edged: it can create a well-ordered society of rule-followers, but also a society where freedom is only an illusion, quietly given up in exchange for the feeling of security.

Read more about the debate on privacy and surveillance here.

Conclusion: From the Panopticon to the Digital Self – Are We All Wardens Now?

The journey of Panopticism from a prison blueprint to a pervasive social condition is a story about the psychology of control. Jeremy Bentham’s 18th-century insight – that surveillance could “grind rogues honest” by making them watch themselves – has evolved into a central organizing principle of the modern world.

Michel Foucault warned us how this principle spread through every institution, subtly chaining minds even where bodies walked free. And today, in our globally networked, data-intensive society, we find that the chains have in some ways moved inside our heads. We carry the sense of being watched with us, and it influences countless tiny decisions each day: what we say, where we go, what we search, how we present ourselves.

We have seen that Panopticism is not inherently partisan – it is a tool that can be used for maintaining social order or for imposing hegemonic control. What remains constant is the mechanism: leveraging the human tendency to self-regulate under an observing eye.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of our current era is that many of us have willingly installed that eye in our lives (via smartphones, social media, smart home devices). We have, in effect, become complicit in our own surveillance to an unprecedented degree – for the convenience, connectivity, and security it provides.

In doing so, we have empowered not only authorities above us to watch, but peers all around us. We are each a node in the watching network – observed by others and observing others in turn.

So, have we truly turned into our own wardens? In many respects, yes. We check ourselves more than ever, often without needing a reminder from any authority. The architecture of digital platforms and public surveillance has made panoptic self-discipline a default mode of living. We often anticipate the consequences of stepping out of line before anyone else need intervene.

In a way, society runs on autopilot: billions of mini-wardens making sure billions of “prisoners” (who are also themselves) behave.

Yet, it’s not a perfect Panopticon. There remain blind spots, acts of rebellion, and calls for reform. The psychology of control that Panopticism embodies is powerful, but so is the human spirit for freedom.

We conclude with a contemplative note: As we continue to weld the keys of our own social jail cells, perhaps we should pause and ask who benefits from this arrangement and at what cost?

True freedom may require that we sometimes step out of the watchtower’s light and reclaim the dark, unobserved corners where honest, unguarded life can flourish. The balance between safety and liberty, between social order and personal autonomy, will be an enduring challenge.

Panopticism has shown us the mechanism of self-control; it is up to us as a society to decide how and when to apply the brakes on that mechanism. After all, a society of self-wardens might be orderly, but the measure of a healthy society is not only how well people behave under watch – it’s how well they thrive in privacy and freedom.

The ultimate question that Panopticism poses in the digital age is whether we can guard our safety without fully surrendering the keys of our mind to the sentinel we have internalized.

It’s a question we are collectively still trying to answer, as we peer into the all-seeing eye of the future.

Read more about Panopticism and self-surveillance here.