I. A New Kind of Crisis Management

The term “climate lockdowns” didn’t begin in parliaments or policy papers — it emerged on the fringe, first as speculation, then as a provocative warning. But increasingly, what was once dismissed as conspiracy rhetoric is now surfacing in serious discussions. Academics, think tanks, and policy influencers have begun to ask: what if the only way to avoid ecological collapse is to impose restrictions on human activity, much like we did during the pandemic?

To many, this sounds like common sense — a rational response to a global emergency. But to others, it raises a disturbing possibility: that in the name of saving the planet, governments may normalize a form of social control that would have once been politically unthinkable.

If climate change is framed as a permanent crisis, what does that do to the boundaries of state power? And what might it mean for the average citizen — not just now, but in the world we’re creating for future generations?

II. What Are Climate Lockdowns?

🛑 Definition and Framing

“Climate lockdowns” is not yet a formal policy term — but it has been used to describe a proposed future in which governments impose restrictions on personal freedoms in the name of environmental sustainability.

These could include:

-

Banning or limiting private car use

-

Restricting air travel

-

Instituting carbon rationing for individuals

-

Limiting meat consumption

-

Reducing work-related commutes through mandatory remote work

The rationale is rooted in precedent: during COVID-19 lockdowns, global carbon emissions dropped dramatically. Satellite imagery showed clearer skies, wildlife returned to cities, and pollution levels plunged. This led some environmentalists to suggest that, in an emergency, radical measures do work — and should perhaps be considered again, but for the planet instead of public health.

What’s critical to understand is that climate lockdowns may not arrive as a single, sweeping declaration. Instead, they may emerge piecemeal — through technocratic measures, “nudges,” and policy changes that frame restrictions as responsible choices.

III. The Origins: Where the Idea Came From

🧠 Mariana Mazzucato and the Project Syndicate Paper

The first significant use of the term in mainstream circles came from economist Mariana Mazzucato. In a 2020 article published by Project Syndicate, she wrote:

“In the near future, the world may need to resort to lockdowns again—this time to tackle a climate emergency.”

Mazzucato was not advocating authoritarianism — she was warning that if transformative action isn’t taken proactively, then reactive restrictions might become necessary.

That article, cited and debated widely, set off a wave of interest and suspicion. Suddenly, climate lockdowns were no longer just speculative — they were on the record.

Her warning wasn’t “we should lock down for climate change.” It was: “if we don’t act now, governments may conclude they have no choice.” But many readers, wary from the pandemic, heard something different: preparation for coercion.

IV. Lessons from the Pandemic: Proof of Concept?

🧪 Pandemic Precedent

The global response to COVID-19 introduced something unprecedented: near-total behavioral control justified as a moral and scientific imperative. In democratic societies, citizens accepted movement restrictions, curfews, digital health passports, and mass surveillance — many for the first time in their lives.

The pandemic didn’t just change policy — it changed psychology. It taught institutions that behavioral change at scale is possible, and taught populations that restrictions can be normalized.

Environmental policymakers were watching. If science could justify a hard stop to daily life — and if citizens could be convinced or compelled to comply — then the machinery for a more controlled society already existed.

Of course, the pandemic was acute and time-bound. But what happens when the “emergency” is open-ended, like climate change? With no clear finish line, the justification for restrictions could stretch indefinitely — and so could the restrictions themselves.

V. From Speculation to Policy Language

🏙️ 15-Minute Cities and Urban Planning

The “15-minute city” model proposes that all essential services — work, shopping, education, healthcare — should be accessible within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from one’s home. Paris, Melbourne, Barcelona, and Oxford are piloting versions of this model.

On the surface, it sounds efficient and environmentally friendly. But critics warn that this design philosophy could evolve into geo-fenced movement zones, where travel outside one’s “designated area” is restricted, monitored, or disincentivized.

In Oxford, UK, a traffic-filtering scheme designed to reduce congestion was met with public backlash — some residents feared it was the start of movement permissions. While local officials insisted that freedom of movement would be preserved, the controversy revealed a growing public sensitivity to policies that limit autonomy, even in the name of sustainability.

💳 Personal Carbon Allowances

A 2021 paper in Nature Sustainability suggested that each individual could be allocated a carbon allowance — a set amount of “carbon credits” per year. These would be deducted automatically through digital payment systems based on your consumption patterns: food, travel, energy, and goods.

This idea, once purely academic, is now being taken seriously by policymakers in parts of the EU and China. Carbon budgeting tools are already appearing in consumer banking apps as “voluntary features” — but for how long?

If participation becomes mandatory, or tied to incentives, the line between personal choice and centralized management may become very thin.

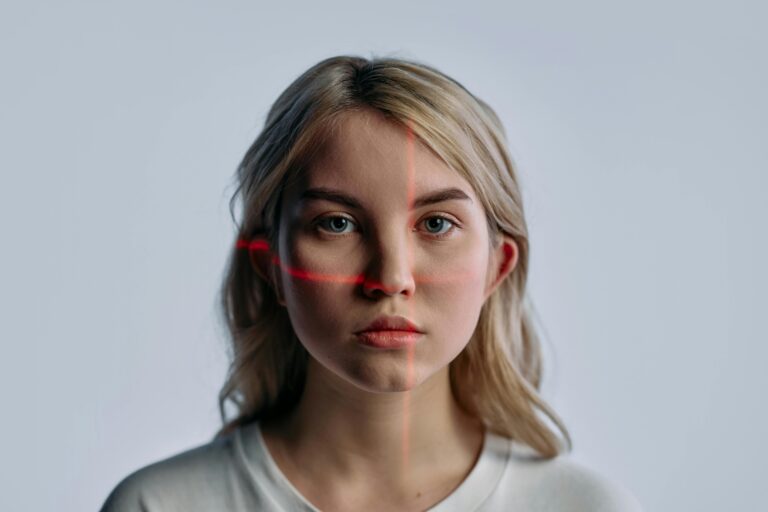

VI. Surveillance Tech and Digital Enforcement

📱 From Monitoring to Management

The technology that would enable climate lockdowns is already here. From smart meters that track home electricity use, to license plate recognition systems that track vehicle movement, to payment platforms that flag carbon-intensive purchases — the infrastructure for real-time behavioral monitoring is largely built.

China’s Social Credit System offers a glimpse into how data streams can be consolidated into compliance scores — and how those scores can be used to determine access to loans, transport, or even schooling. While Western countries have not adopted this model explicitly, many are moving toward ESG-linked digital identity systems, particularly in banking and corporate compliance.

This data could be used to encourage — or enforce — low-carbon behavior. What begins as a “green points” reward system could morph into penalties or restrictions based on real-time consumption patterns.

VII. Media Narratives and Cultural Framing

🧠 The Psychology of Moral Emergency

Media coverage of climate change has increasingly adopted urgent, apocalyptic language: “code red for humanity,” “the planet is on fire,” “irreversible tipping points.” These narratives may reflect scientific consensus — but they also activate powerful psychological responses.

When people are frightened and feel morally implicated, they are more willing to accept restrictions. The messaging not only emphasizes threat but assigns blame — not just to fossil fuel companies or governments, but to individual behaviors.

This creates a powerful dynamic: fear + guilt = compliance.

📺 Normalization Through Storytelling

Films, school programs, documentaries, and advertising are all part of a growing cultural ecosystem that treats carbon-reduction not just as wise — but morally virtuous. Opting out, resisting, or even questioning certain policies may increasingly be seen as anti-social, or even anti-human.

This cultural shift may lay the groundwork for public acceptance of more invasive measures — especially if those who resist are portrayed not as citizens, but as enemies of progress.

VIII. The Appeal of Climate Lockdowns to Power

🔐 Crisis as Opportunity

Every major crisis offers a moment of opportunity — and those in power rarely let it go to waste. Climate policy offers:

-

Moral justification: framed as protecting future generations

-

Technocratic framing: rooted in data, modeling, and scientific consensus

-

Behavioral control: enforced through digital platforms already in place

This trifecta makes climate governance uniquely potent — and uniquely prone to abuse. Policies that might once have sparked backlash may now be introduced gradually, with climate as a permanent emergency backdrop.

As philosopher Giorgio Agamben warned, when a society begins to operate under permanent states of exception, freedom becomes negotiable — and ultimately dispensable.

IX. Pushback and the Emergence of Counter-Narratives

💬 Public Resistance Grows

In recent years, a new wave of environmental skepticism has emerged — not climate denialism, but climate policy criticism. This includes:

-

Farmers protesting emissions-based land grabs

-

Citizens opposing geo-fencing travel zones

-

Legal challenges to personal carbon budgeting systems

These movements are not always anti-environment — but they are deeply skeptical of centralized solutions that limit autonomy without consent.

🤖 Dismissal as Conspiracy

Many of these critiques are labeled misinformation or conspiracy. And while some truly are speculative or unfounded, this sweeping dismissal can have a chilling effect — discouraging legitimate debate over how far policy should reach.

If concern over surveillance, restriction, and autonomy is treated as inherently dangerous, then public scrutiny of power becomes socially unacceptable — and that, ironically, is how democracies erode.

X. Philosophical Questions: Crisis, Freedom, and Trade-Offs

⚖️ When Does Consent Become Coercion?

If policies are introduced under emotional pressure, endorsed by media, and enforced via algorithm, is that democratic governance — or emotional blackmail?

The line between persuasion and coercion blurs when dissent is equated with immorality.

🧭 Responsibility vs Autonomy

We need climate solutions. But who gets to define them? Is the future shaped by centralized models and top-down enforcement, or by voluntary shifts, local innovation, and decentralized resilience?

This is the crux of the debate: environmental action vs technocratic authority. The two are not synonymous — and we must be careful not to conflate them.

XI. The Future: What’s Next?

📆 Scenario 1: Gradual Lockdown Normalization

As technologies improve and social pressure mounts, climate lockdown-style policies may become more common — starting as voluntary, then becoming default, and eventually mandatory.

📆 Scenario 2: Populist Pushback

Widespread discontent with technocratic overreach could lead to populist movements that reject environmental policy altogether — undermining real progress in favor of political backlash.

📆 Scenario 3: Transparent Reform

The ideal outcome? A robust, public-facing debate on the ethics, limits, and goals of climate governance — where sustainability is balanced with liberty, and where trust replaces control.

XII. Conclusion: The Thin Line Between Necessary and Normalized

Climate change is real. Its dangers are profound. But so is the danger of using crisis as a long-term justification for behavioral management — especially when it’s enforced digitally, quietly, and without debate.

Climate lockdowns may never arrive as a single directive. But step by step, through nudges, regulations, and algorithms, a system of conditional participation could emerge.

The question is not whether action is needed. The question is: how much control should a crisis justify — and for how long?