I. Introduction: When Convenience Redraws the Map of Autonomy

In the 20th century, owning a car was one of the clearest markers of personal freedom. It signified independence — the ability to go where you want, when you want, without relying on anyone else. It meant mobility, privacy, and self-reliance. But in the 21st century, that cultural and practical freedom is quietly being recast as an ecological burden and a social inefficiency.

A growing coalition of urban planners, policymakers, and global institutions are now advocating for a world with fewer — or no — personally owned vehicles. This movement isn’t led by dramatic legislation, but by gradual policy shifts, infrastructure changes, behavioral nudges, and the emergence of alternative transportation frameworks like Mobility as a Service (MaaS).

It’s not being sold as a ban on car ownership, but the outcome may resemble one.

In this article, we explore the forces behind this transformation, the implications for privacy and freedom, and the ideological frameworks that justify replacing individual mobility with centralized control — all under the banner of sustainability.

II. The New Narrative: From Driver to Passenger

While few governments have explicitly proposed banning car ownership, many are shaping policies that discourage it — through environmental regulation, urban planning models, and economic disincentives. The justification is multifaceted: climate change, public health, urban congestion, and economic equity.

🌍 Global Institutions and Framing

In 2016, the World Economic Forum published a vision of future cities where “you’ll own nothing and be happy” — a provocative phrase that included the idea of shared transport replacing private cars. Framed as environmentally necessary and socially inclusive, this vision suggests that owning a vehicle is not only inefficient, but undesirable.

🇪🇺 European Policy Shifts

In 2021, the Scottish Government pledged to reduce car travel by 20% by 2030, in part by “changing behaviors” around car ownership. Meanwhile, Dutch and German urban planners are redesigning cities to prioritize public transport and bicycles over cars, while removing or repurposing parking spaces to make driving more difficult and less necessary.

🇺🇸 U.S. Policy Trends

In the United States, California announced plans to phase out sales of new gas-powered vehicles by 2035. While this doesn’t outlaw car ownership, it accelerates a shift toward electric vehicles and opens the door to tighter controls on how — and whether — cars can be used in the future.

These moves represent a global trend: from enabling ownership to managing mobility.

III. Mobility as a Service (MaaS): A New Framework for Movement

Central to this transition is the concept of Mobility as a Service, or MaaS — an emerging transportation model that replaces private vehicles with on-demand, digitally managed access to various transportation modes: trains, e-bikes, rideshares, autonomous taxis, and more.

In theory, MaaS optimizes traffic flow, reduces emissions, and improves access to mobility for underserved populations. It’s often presented as a win-win: less traffic, lower emissions, fewer accidents, and more equitable transit.

But there’s a critical difference between access and ownership — and between options and permissions.

When mobility becomes a service, it becomes conditional. It is delivered — or denied — not by the turn of a key, but by a decision made elsewhere: a company, an algorithm, a policy.

IV. The Environmental Argument: Policy with an Expiration Date

The most common justification for reducing or ending car ownership is the climate crisis. The environmental footprint of gas-powered vehicles — and to a lesser extent, electric vehicles — is cited as a reason to promote dense, car-free urban design.

🔋 Electrification Is Not Neutral

While EVs are often held up as a clean alternative, their environmental impact is not negligible. Battery production, energy source variability, and resource extraction all carry ecological costs. As a result, some climate advocates now argue that replacing combustion engines with EVs is not enough — the number of vehicles overall must drop significantly.

🧮 Carbon Accounting and Personal Quotas

Some policymakers have proposed individual carbon budgets, where driving (among other activities) is counted against a personal environmental allowance. If tied to payment apps or digital IDs, this model could enforce restrictions on travel or vehicle use — even if the individual owns the car.

This vision shifts the burden of change from institutional reform to individual behavior — a move that requires surveillance, compliance, and eventually, enforcement.

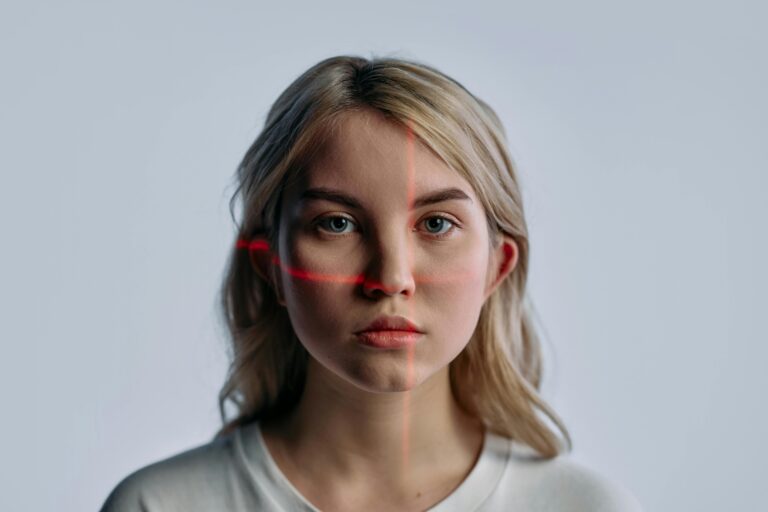

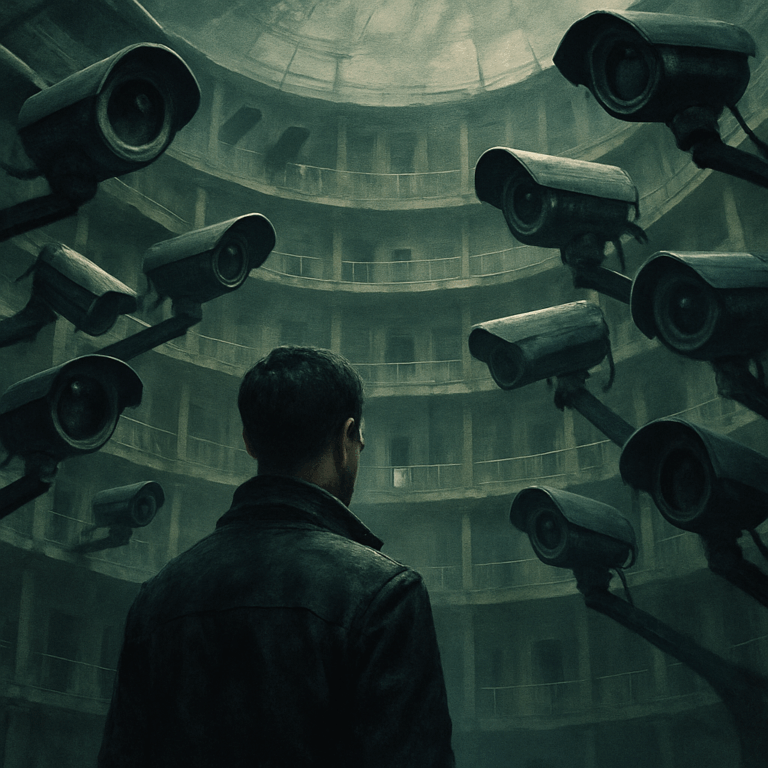

V. Surveillance by Design: When Movement Requires Permission

Reducing car ownership does not only change how people move — it changes how they are monitored.

Digital transportation platforms (like Uber, Lime, or city-wide bike shares) already collect location, payment, and behavioral data. When such systems become the norm, this data is not just used for routing — it becomes infrastructure for social management.

🧠 Predictive Enforcement and Geo-Fencing

As smart cities grow, AI systems can identify “anomalous behavior” in real time. Geo-fencing — digital boundaries that restrict vehicle movement in certain areas — has already been tested for emissions zones and protest suppression alike. In a future MaaS system, entering the wrong zone or exceeding your usage quota could automatically trigger a fine — or disable your access to transport altogether.

🔗 The External Link – Real-World Example of Geo-Fencing

Cities like London and Beijing already use emissions-based geo-fencing. For instance, London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) leverages automated number plate recognition and cross-references it with vehicle data to impose fees on non-compliant drivers.

👁️ Behavioral Nudging via App-Based Access

Ride-hailing and micro-mobility apps can dynamically adjust pricing or access based on user behavior. Late-night trips might be discouraged. Unapproved destinations might be priced prohibitively. Personal scores — based on punctuality, spending patterns, or carbon output — could be used to prioritize access during peak times.

In such systems, autonomy is replaced by conditional access.

VI. Cultural Implications: Redefining Freedom by Design

Cars are more than transportation — they’re cultural artifacts. They feature in music, film, literature, and identity. To many, especially outside dense urban centers, cars represent independence, resilience, and mobility — not luxury.

The move toward eliminating car ownership is therefore not just logistical. It’s ideological. It redefines freedom not as the ability to go where you please, but as the privilege of access within approved systems.

VII. Who Benefits from a Ban on Car Ownership?

The shift from private ownership to corporate-managed mobility platforms isn’t just about sustainability — it’s also a massive business opportunity.

-

Tech Giants like Apple and Google are developing autonomous vehicle systems that depend on integrated digital ecosystems.

-

Ride-hailing Companies like Uber envision a future where car ownership is obsolete and every journey is monetized through their apps.

-

Insurance and Finance Firms benefit from a pay-per-use model, where every mile, behavior, and destination becomes a data point.

In this model, the freedom to move is not removed outright — it is monetized, tracked, and increasingly conditioned on social and environmental behavior.

VIII. A Two-Tier Future: Privilege vs. Compliance

One likely outcome of this transition is a bifurcation of mobility rights.

-

The Privileged Few — who can afford private EVs or who live in areas not subject to restrictions — will retain traditional freedoms.

-

The General Public — especially in urban environments — will be nudged, priced, or pressured into using managed transport systems, with limited ability to opt out.

Such a system risks creating not just a mobility divide, but a behavioral compliance economy, where dissent or deviation from sanctioned norms could carry real-world limitations — not just social, but physical.

IX. Ethical Questions: Sustainability Without Autonomy?

To be clear, reducing traffic, improving air quality, and rethinking urban design are all valuable goals. But the means matter.

When environmental policies are used to justify centralized control, restricted access, or mass surveillance, they risk undermining the very democratic values they claim to protect.

Should your ability to move be contingent on an AI’s interpretation of your carbon footprint?

Is it ethical to restrict movement based on predictions of risk or non-compliance?

And perhaps most importantly: What happens when digital infrastructure removes not only the need to own, but the right to choose?

X. Toward a Rational Approach: Sustainable and Free

The debate over car ownership should not be framed as a binary between reckless freedom and responsible collectivism. There is room for innovation — electric vehicles, car-sharing, improved transit — without dismantling autonomy.

Policymakers and planners must:

-

Ensure that alternatives to car ownership are additive, not coercive.

-

Preserve meaningful privacy and choice in transportation decisions.

-

Prevent corporate monopolies from becoming the new gatekeepers of movement.

A future built on sustainability must also be built on consent — not just to what we give up, but to how, and why, we give it up.

XI. Conclusion: Steering Toward the Future — Or Being Driven There?

The growing push toward shared mobility may improve some urban outcomes. But it also signals a deeper cultural and political shift: from self-determination to soft management — from freedom of movement to managed mobility.

Whether or not there is ever a formal ban on car ownership, the effect may be functionally similar: a world in which only a small segment of society can truly go where they please, when they please — while the rest live within the boundaries of digitally monitored, corporately managed permission.

The car, for all its flaws, once represented something ungoverned and open-ended.

We should think carefully before trading that in — not just for a subscription, but for a score.