📲 I. Introduction: When Smart Becomes Watchful

Smart devices have quietly embedded themselves into the fabric of modern life. From smartphones and wearable tech to smart fridges and voice assistants, convenience has been the selling point — frictionless connectivity, personalized recommendations, remote control of the home. But what many users don’t realize is that these conveniences are powered by systems that collect, analyze, and often monetize personal data at an unprecedented scale.

As artificial intelligence (AI) becomes more deeply integrated into consumer technology, a new kind of surveillance has emerged — not just observation, but interpretation. These systems don’t merely record what we do — they infer who we are, what we’re likely to do next, and whether our behavior aligns with what’s considered “normal,” “desirable,” or “compliant.”

What we’re witnessing is the rise of AI surveillance in smart devices — a trend that poses increasingly complex challenges for privacy, autonomy, and democratic norms.

⚙️ II. The Mechanisms Behind the Monitoring

The majority of smart devices today function as nodes in an invisible network of data exchange. Seemingly innocuous activities — watching a show, making a purchase, adjusting a thermostat — can generate behavioral data that feeds into large AI models.

🔹 Smartphones and Apps

Smartphones are perhaps the most pervasive surveillance devices ever created. App permissions often include access to microphones, cameras, location data, motion sensors, and browsing activity. Many users grant these permissions automatically, unaware that even unused apps can collect data in the background. In some cases, third-party SDKs embedded in apps quietly funnel this data to advertisers, brokers, or parent companies for profiling.

🔹 Smart TVs and Streaming Devices

Smart TVs use ACR (Automatic Content Recognition) to monitor not only the shows you watch, but also how long you watch them, whether you skip ads, and even what external content is playing through HDMI. This data is cross-referenced with broader media habits to build detailed psychographic profiles. Most users are unaware that their viewing habits can be shared with advertisers — or used to predict political leanings and emotional states.

🔹 Voice Assistants and Home Devices

Devices like Alexa, Siri, and Google Assistant rely on constant passive listening to detect voice commands. Although they are designed to activate only when prompted, investigations have shown that these devices sometimes record unprompted conversations — occasionally storing audio clips on cloud servers without users’ full knowledge or consent.

🔹 Wearables and Fitness Trackers

Health-focused devices track heart rate, sleep patterns, physical activity, and location — all of which feed into datasets that can reveal everything from stress levels to potential health risks. Insurance companies and employers have shown increasing interest in integrating this data into health plans and productivity evaluations.

🧾 III. From Passive Tracking to Behavioral Scoring

What distinguishes AI surveillance in smart devices from traditional data collection is its inferential nature. AI doesn’t just collect — it analyzes. It learns. And increasingly, it evaluates.

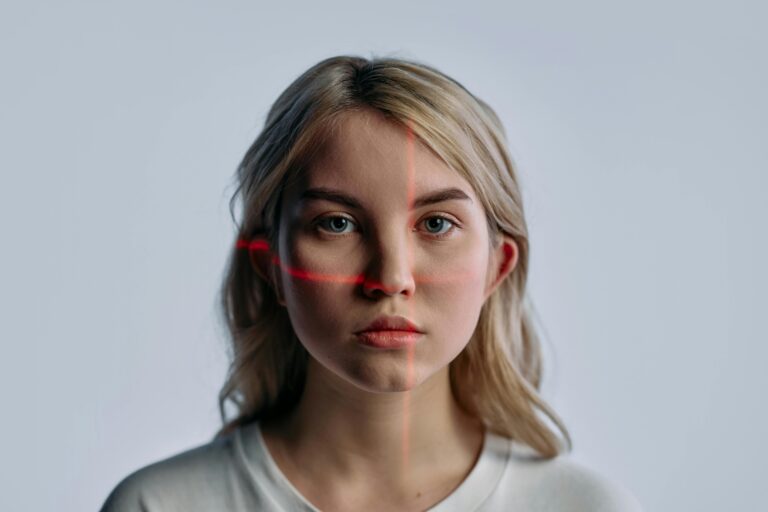

🔸 Predictive Behavior Modeling

AI algorithms trained on your personal data begin to predict future actions — when you’re most likely to buy, whether you’re depressed, how productive you are, even how much risk you represent to an institution.

In China, behavioral scoring systems already influence everything from loan eligibility to travel freedom. But similar logic is creeping into Western systems — albeit less explicitly.

🔸 Workplace Productivity Scores

Some companies now deploy AI to monitor employees’ keystrokes, webcam usage, and screen activity — assigning performance scores that affect performance reviews, promotions, or job security. Critics argue this reduces workers to data points while fostering a culture of constant, passive scrutiny.

🔸 Social Risk Profiling

As platforms experiment with “trust scores,” an individual’s behavior across multiple apps may soon affect more than just recommendations. A flagged pattern on social media or an unusual speech tone detected by voice AI could one day influence credit limits, insurance rates, or travel permissions.

Behavioral scoring is not merely about preferences — it’s about power. It creates a tiered system where access, opportunity, and even legitimacy can be silently altered by invisible algorithms.

A 2023 report by Brookings Institution explored how these practices are evolving and called for clear AI oversight frameworks to protect against invisible scoring mechanisms affecting core rights. (Read the Brookings report)

🧱 IV. Historical Roots: Surveillance Capitalism and Digital Normalization

The current landscape of AI surveillance in smart devices didn’t emerge overnight. It reflects the evolution of what Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff called “surveillance capitalism” — a model in which personal experiences are commodified and sold as predictive products.

The first wave began with targeted ads. Browsing habits, location tracking, and online purchases were leveraged to create increasingly precise marketing tools. But as the model evolved, the emphasis shifted from predicting behavior to shaping it. Feedback loops were created: nudges, notifications, subtle UX changes — all designed to direct choices in measurable ways.

As AI grew more capable, so did its applications — extending far beyond commerce into finance, governance, education, and health. The digital footprint became a behavioral signature, and algorithms began writing the script of daily life.

🔒 V. Consent and Control in the Age of Passive AI Surveillance

One of the most insidious aspects of modern surveillance is its opacity. The data flows are invisible. The permissions are buried in Terms of Service. And the outputs — behavioral scores, trust ratings, risk assessments — are seldom shared with the people they affect.

This raises ethical and practical concerns:

-

Informed consent becomes a fiction if users don’t fully understand what they’re agreeing to.

-

Appeal mechanisms are rare or non-existent for algorithmic decisions.

-

Data reuse blurs the boundary between commercial profiling and institutional control.

This opacity is particularly dangerous when used to automate access to essential services: banking, healthcare, housing, and education. In such cases, the user is not simply being surveilled — they are being sorted.

🧠 VI. Psychological Impacts: The Internalization of AI Surveillance

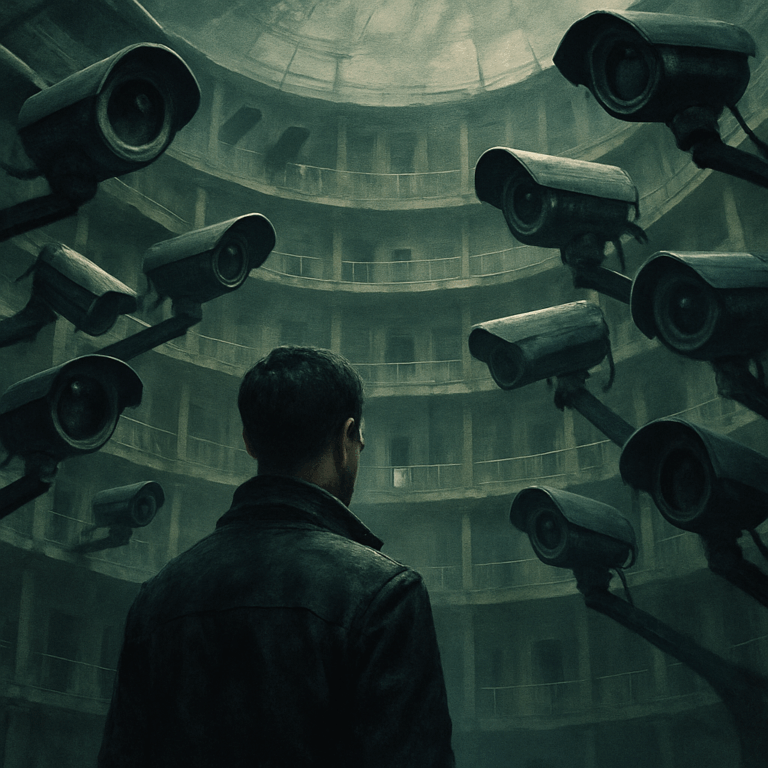

The knowledge — or even suspicion — of being watched alters human behavior. This is the principle behind the panopticon, a metaphor popularized by philosopher Michel Foucault. In a panopticon, the uncertainty of observation leads individuals to regulate themselves — not because they are being forced to, but because they might be watched.

This “soft control” is amplified by AI systems, which monitor not only what you do, but how consistently and how predictably you behave. The psychological effects are subtle but powerful:

-

People may censor their speech around voice assistants.

-

Employees may alter behavior in front of work devices.

-

Children may grow up under constant observation, normalizing self-monitoring as virtue.

Over time, surveillance becomes a condition of participation — not an exception, but an expectation.

🧬 VII. The Slippery Slope: What’s Coming Next?

The direction of travel is clear. As AI models grow more powerful and interconnected, AI surveillance in smart devices will likely expand into:

-

Insurance: Premiums based on health trackers, movement patterns, or inferred risk behaviors.

-

Banking: Creditworthiness augmented with online behavior or political associations.

-

Retail: Dynamic pricing or access restrictions based on consumer profiles.

-

Education: Adaptive learning systems that flag students for attention based on biometric feedback or tone of voice.

Some of these innovations may improve efficiency or access. But without transparency, regulation, and the right to opt out, the same tools can easily be used to entrench inequality and control.

🛠️ VIII. Resistance and Alternatives: The Case for Redundancy

Resisting this trajectory doesn’t require abandoning technology — but it does require critical engagement. Some practical steps include:

-

Decentralized tools: Use devices and platforms that prioritize privacy and open-source transparency.

-

Policy pressure: Advocate for AI regulations that guarantee user rights, transparency, and recourse.

-

Digital literacy: Educate the public about how data is used and what alternatives exist.

-

Redundancy planning: Build parallel systems — analog, local, human-centered — that can function independently of centralized, algorithmically managed infrastructure.

Resistance begins not in rejection, but in redundancy. Systems that preserve privacy and autonomy must be viable — not merely principled.

🧭 IX. A Final Thought: Autonomy in the Algorithmic Age

The rise of AI surveillance in smart devices represents more than a privacy issue. It’s a philosophical challenge — to the very notion of what it means to act freely in a world where choices are preemptively shaped by invisible systems.

In such a world, the most subversive act may be simply to pause. To question. To say, “I’m not sure I agree.” Because AI cannot function without patterns — and the refusal to be easily categorized is its greatest disruption.

Autonomy is not the absence of influence — but the capacity to recognize it. And in an age of smart devices, that capacity may be the first freedom worth protecting.